ブログ

Serving foreign judicial documents in Japan [Japan Trademark & Design Update]

2021.09.10

Serving foreign judicial documents in Japan [Japan Trademark & Design Update]

Akihiro Tomomura

https://www.tmi.gr.jp/uploads/2021/07/26/jptu_issue18.pdf#page=6

Introduction

Many Japanese companies are now involved in patent infringement litigation or other proceedings around the globe. If a lawsuit is filed in a foreign court against a Japanese company that has no subsidiaries or business offices in the foreign state, the foreign court has to serve the relevant judicial documents (such as a complaint) on the defendant in Japan. Such service of foreign judicial documents, however, falls within the exercise of jurisdiction, which cannot be carried out by a foreign court in Japan without Japan’s judicial assistance. This article briefly introduces the methods for serving foreign judicial documents in Japan.

Framework of the methods to obtain judicial assistance in Japan for foreign proceedings

The methods to obtain judicial assistance in Japan for foreign proceedings vary depending on the existence and contents of the bilateral or multilateral conventions between Japan and the foreign states at issue.

Service under the Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters (the “Hague Service Convention”) is one of the most commonly used methods in practice. *1 Japan is a signatory to the Hague Service Convention and has agreed to respond to other signatories to the Hague Service Convention should they request Japan to serve documents concerning civil or commercial cases under the rules thereof. *2

Japan is also a signatory to the Convention Relating to Civil Procedure (the “Hague Civil Procedure Convention”). A state that is not a signatory to the Hague Service Convention but is a contracting state to the Hague Civil Procedure Convention is able to request Japan’s judicial assistance thereunder. *3 *4

In the event of a state that is not a party to these Conventions requesting Japan’s judicial assistance, Japan responds to such request in accordance with relevant domestic law; namely, the Act Relating to the Reciprocal Judicial Assistance to be Given at the Request of Foreign Courts. *5 Such Act stipulates that, at the request of foreign courts, Japanese courts shall provide assistance in serving documents, etc., provided that the request shall, inter alia, come through diplomatic channels. *6

Service of process in Japan for proceedings in a foreign state under the Hague Service Convention

■Formal service (Art. 5(1))

Art. 5(1) of the Hague Service Convention provides two methods – (a) a method prescribed by the laws of Japan for the service of documents, and (b) a particular method requested by the applicant. The latter method can be carried out unless it is incompatible with the laws of Japan.

An appropriate authority or judicial officer in a contracting state to the Hague Service Convention can make a request to Japan’s central authority to serve its judicial document in Japan in accordance with Art. 5(1). Japan has designated the Minister of Foreign Affairs in Japan (“MOFA”) as its central authority which accepts incoming requests for service. The request must be written in English, French or Japanese.

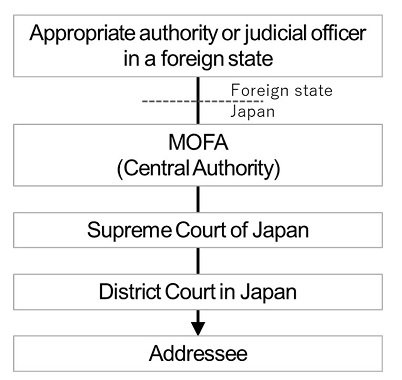

As shown in the chart below, upon receipt of a request, MOFA refers the document to the Supreme Court of Japan and the document is then forwarded to a district court in Japan that has jurisdiction over the addressee. Where the document to be served is a complaint, it will be served via the district court using a process called tokubetsu-sotatsu which is a special type of court mediated service by mail.

Once service is effected, a certificate of service then passes to the requesting authority through the same channels in reverse. In a case where the document cannot be served, a certificate setting out the reasons preventing service is prepared. *7

With respect to the timing involved, it generally takes around four months for foreign proceedings to be effectively served in Japan under the Hague Service Convention, from the time when MOFA receives the request from the requesting state, to the time when MOFA transmits the service result to the requesting state. *8

It must be emphasized that the MOFA requires full Japanese translations to be attached for any document to be served in Japan. *9 However, even if some parts of the documents are not translated, the documents can still be served as an informal/voluntary service pursuant to Art. 5(2) of the Hague Service Convention unless such service has not been intentionally deleted in the request form.

■Informal/voluntary service (Art. 5(2))

Furthermore, under Art. 5(2) of the Hague Service Convention, a judicial document may be served by delivery, with or without its full translation, to an addressee who accepts it voluntarily.

In such case, a court clerk at the district court uses regular mail to notify the addressee of the document to be served, and the addressee can accept it by appearing by itself or through its proxy or request the court to forward the document. In a case where the addressee fails to respond to the court within three weeks from the date of notification, the informal/voluntary service is deemed to be refused. When the informal/voluntary service is refused, the request is returned unexecuted.

■Direct service through diplomatic/consular channels or by mail

Direct service through diplomatic/consular channels or by mail is not available in Japan.

Art. 8 of the Hague Service Convention permits the service of judicial documents directly through its diplomatic or consular agents unless the signatory country has objected to such service. Art. 10(a) of the Hague Service Convention permits the “sending” of judicial documents by mail unless the signatory country has objected to such service, and some foreign courts have interpreted this as including service of process. *10 However, Japan has declared its opposition to Art. 8 and Art. 10(a) of the Hague Service Convention. *11 As such, service of process in Japan under the Hague Service Convention must be via MOFA as the central authority. *12

Enforcement

As stated above, service of process in Japan can certainly be said to be feasible (with some patience). It should be noted, however, that a served process does not necessarily result in it being easier to enforce foreign judgments in Japan, and Japan is not a party to any bilateral or multilateral treaties regarding reciprocal recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments, such as the Hague Convention on Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters.

A judgment rendered by a foreign court can be recognized in Japan (without the need for a separate procedure) if it satisfies the requirements of the Code of Civil Procedure (the “CCP”). *13 In order to enforce a foreign judgment, the proponent must obtain an enforcement judgment before a Japanese court and then file a petition for compulsory enforcement based on such judgment. A final and binding judgment rendered by a foreign court is valid in Japan if it meets all of the requirements prescribed in the CCP. One of the requirements is that the defendant has been served (excluding service by publication or similar means) a summons or an order necessary for the commencement of the suit or has appeared without receiving such service. *14

Conclusion

As summarized herein, formal service under Art. 5(1) of the Hague Service Convention requires full Japanese translations of a complaint and summons and direct service by mail is no longer available in Japan. Accordingly, it could be significant for a plaintiff who has brought a lawsuit before a foreign court against a Japanese entity to have negotiations wherein the defendant appears before the foreign court without receiving such service or voluntarily accepts the judicial document under Art. 5(2) of the Hague Service Convention, in exchange for giving certain advantages in favor of the defendant, such as an extended time period to respond to the complaint.

*1 A current list of the signatory states and information as to any observations, declarations, or other matters is available on the website of the Hague Conference on Private International Law.

*2 For more detailed protocols regarding requests under the Hague Service Convention, please see https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/000409873.pdf

*3 A contracting state to both Conventions must request Japan’s judicial assistance pursuant to the Hague Service Convention. See Art. 22 of the Hague Service Convention.

*4 For more detailed protocols regarding requests under the Hague Civil Procedure Convention, please see https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/000409874.pdf

*5 Law No. 63 of March 13, 1905, as amended

*6 For more detailed protocols regarding requests under the Reciprocal Judicial Assistance Act, please see https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/000409876.pdf

*7 Reasons preventing service include “moved,” “return unknown,” and “unclaimed.”

*8 The impact brought about by COVID-19 may cause more delays in the service of proceedings.

*9 See Art. 5(3) of the Hague Service Convention.

*10 In the U.S. for example, please see Water Splash, Inc. v. Menon, 137 S. Ct. 1504 (2017).

*11 https://repository.overheid.nl/frbr/vd/004235/1/pdf/004235_Notificaties_70.pdf

*12 Apart from service of process under the Hague Service Convention, service of judicial documents under a bilateral convention, if applicable, is also available. In this regard, Japan has entered into bilateral Consular Conventions between the U.S. and the U.K., respectively.

*13 Act No. 109 of June 26, 1996, as amended.

*14 Art. 118(2) of the CCP.

Member

PROFILE