ブログ

[Digital Yen Blog (iii)] What Are the “Intermediaries” Responsible for Circulating the Digital Yen Eligible Business Types and Regulations (Part 1)

2025.09.19

This post is an English translation of the original Japanese post published on August26, 2024, prepared in response to requests for an English version.

Introduction

For the purpose and background of this blog, please refer to [Digital Yen Blog] Welcome to the Digital Yen Blog! As noted in the post, this blog refers to the central bank digital currency (CBDC) currently under consideration in Japan as the “digital yen” for the sake of clarity and readability.

This post covers the second one from the upcoming topics below:

- How Might the Digital Yen Be Used, and What Would Its Legal Tender Status Mean? (Part 1) (Part 2)

- Intermediaries in the Digital Yen Ecosystem: Who Might Be Involved and How They Could Be Regulated

- Can the Digital Yen Balance Privacy with AML/CFT Requirements?

- What Kinds of Value-Added Services Could Be Built Around the Digital Yen—and Who Would Provide Them?

- Should There Be Limits on Digital Yen Holdings or Interest-Bearing Features?

- What Is the Legal Nature of the Digital Yen? A Claim, a Property Right, or Sui Generis?

- Should “Digital Yen Counterfeiting” Be Treated as a New Criminal Offense?

Cash Distribution Pathways – Where Does Cash Come From?

As a foundation for understanding the role of “intermediaries” in the digital yen framework, it is useful to revisit how physical cash is distributed.

A sudden question: If asked “Who issues cash?”, could you answer instantly?

Perhaps that was too easy—the answer is, of course, the Bank of Japan.*

The Bank of Japan is our country’s sole “issuing bank.” The Bank of Japan Act provides that “The Bank of Japan, as the central bank of Japan, shall issue banknotes and carry out currency and monetary control” (Article 1), and “The Bank of Japan shall issue banknotes” (Article 46(1)). Banknotes issued under this authority are recorded as liabilities on the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet.

* Strictly speaking, the Bank of Japan issues only banknotes. Coins are issued by the government. The Act on Currency Unit and Issuance of Coins stipulates that “The power to manufacture and issue coins shall belong to the government” (Article 4(1)). Under this framework, the Minister of Finance commissions the Japan Mint, an incorporated administrative agency, to manufacture coins (Article 4(2)). (This is often confused with the production of banknotes, which is handled by the National Printing Bureau, a separate body.) Once minted, coins are delivered to the Bank of Japan for issuance (Article 4(3)). In practice, however, both banknotes and coins enter circulation through the Bank of Japan’s cash offices, so this distinction is not always emphasized in daily life.

However, even though the Bank of Japan issues banknotes, you cannot simply visit the Bank of Japan and receive cash directly (on the other hand, damaged banknotes can be exchanged at the Bank of Japan’s head office and branches). So, to whom does the Bank of Japan actually issue cash, and through whom does that cash reach our hands?

The answer is financial institutions such as banks. Banks hold current account deposits at the Bank of Japan (BOJ deposits). This is why the Bank of Japan is often called “the bank of banks.” BOJ deposits, like the deposits we hold with private banks, are a type of deposit contract under the Civil Code (Article 666). Legally speaking, this means that the money deposited by the banks is being kept by the Bank of Japan. (The “Terms and Conditions of Current Account,” which set out the details of these deposits, are published on the Bank of Japan’s website.)

Banks withdraw funds from their BOJ deposits and obtain cash when demand for cash rises, for example, around the end of the month when many companies pay salaries.

At that point, the issuance of banknotes by the Bank of Japan takes place (from an accounting perspective, on the liability side of the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet, “BOJ deposits” are replaced with “Banknotes in Circulation”). Subsequently, after payday, cash reaches us when we withdraw bank deposits from bank counters or ATMs.

In this way, cash is circulated not directly from the Bank of Japan, but indirectly through banks and other financial institutions.

What are Intermediaries for the Digital Yen?

To understand the role of intermediaries for the digital yen, let us first look at the following explanation provided in the Interim Report by the Relevant Ministries and the Bank of Japan Liaison Meeting on Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) published in April 2024 (the “Interim Report”):

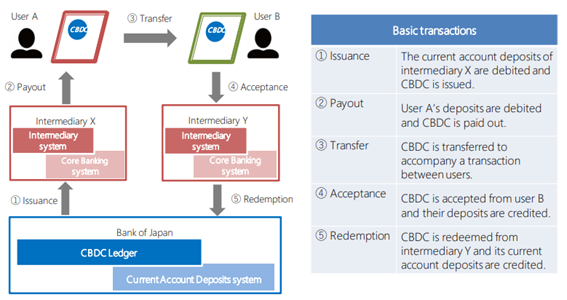

“In the two-tiered model, intermediaries would provide services related to the issuance, distribution, and redemption of CBDC, mediating between the BOJ and CBDC users. Specifically, they would act as a counterparty to the BOJ when undertaking operations regarding the issuance and redemption of CBDC to provide basic payment services to CBDC users. Furthermore, they would act as a counterparty to CBDC users to whom they are responsible for opening/closing accounts, customer management, providing interfaces, and operations regarding distribution of CBDC such as payout, transfer, and acceptance (hereinafter referred to as core services).” (Section 3. (1)(ii))

The first important point is that the role of intermediaries in the digital yen mirrors the role of banks in the case of cash. As discussed above, cash is not issued directly by the Bank of Japan to the public, but rather circulates indirectly through banks and other financial institutions. Similarly, in the case of the digital yen, intermediaries are expected to stand between the Bank of Japan and users, receiving issuance from the Bank of Japan and handling circulation to users.

Let’s look at the life cycle of the digital yen in more concrete stages:

First, the digital yen is issued when an intermediary redeems its current account balance at the Bank of Japan. Second, the digital yen is paid out to users when they redeem deposits or other claims against the intermediary. Third, it can then be used for settlements between users. Fourth, it can be deposited back with an intermediary as a deposit. Fifth, it is redeemed when the intermediary deposits it with the Bank of Japan as a current account balance.

(Excerpt from page 8 of the Interim Report of the Liaison and Coordination Committee on Central Bank Digital Currency)

The next important point is that intermediaries are expected to handle “procedures for opening and closing transactions, customer management, and the provision of interfaces.”

Cash is a tangible object, and since its method of use is extremely simple—merely handing it over to the counterparty—anyone can hold and use it relying solely on their own ability. For this reason, there is no such thing as “procedures for using cash” or “interfaces for using cash.”

By contrast, the digital yen is intangible (data), and in order to hold and use it, digital technology is required. In particular, the digital technology used to hold and use digital currency is generally called a “wallet,” which literally functions as a wallet for digital currency by enabling users to hold it or transfer it to others. For example, in the case of crypto-assets such as Bitcoin, “crypto-asset exchange service providers” under the Payment Services Act offer wallet services for crypto-assets. Thanks to these services, even individuals without the technology or capability to directly participate in the Bitcoin network can still trade Bitcoin. (Although Bitcoin has no issuer and is therefore not identical, in principle it resembles cash or the digital yen in the sense that it circulates to end users indirectly through intermediaries such as crypto-asset exchange providers.)

That intermediaries provide “procedures for opening and closing transactions, customer management, and interfaces” for the digital yen, put simply, means that intermediaries (importantly, not the Bank of Japan) will provide “digital yen wallets”. Accordingly, if in the future we wish to use the digital yen, a typical scenario would be to install an app called “Bank A Digital Yen Wallet” released on a smartphone app store by Bank A (assuming Bank A serves as a digital yen intermediary), complete the onboarding procedures within the app, and, in coordination with Bank A’s internet banking app, transfer digital yen from our deposit account into the wallet as needed for payments and remittances.

Coming Next: Business Types and Regulations for Intermediaries

In the next article, we will consider what types of businesses could actually serve as “intermediaries,” as well as potential regulations that might apply to them.

Member

PROFILE