ブログ

IP High Court Rules on the Scope of Patent Rights After Extension and Awards approx. USD 140M in Damages Against Generics – Appeal 2021 (Ne) No. 10037 (“REMITCH® Case”) –

2025.12.02

Introduction

On May 27, 2025, the Intellectual Property High Court (“IPHC”) issued a significant ruling in a patent litigation filed by the originator pharmaceutical company against generics, alleging infringement of its patent rights during a Patent Term Extension (“PTE”); (2021 (Ne) No. 10037, known as the REMITCH® case).

Reversing the Tokyo District Court decision, the IPHC held that the Defendants’ generic products fell within the technical scope of the patented invention and that the extended patent right validly covered the manufacture and sale of the generics, and ordered the Defendants (generic manufacturers) to pay approximately JPY 21.7 billion (around USD 140 million) in damages, drawing significant attention in the pharmaceutical and IP communities.

The key issues addressed in this judgment include the interpretation of the term “active ingredient (有効成分)” in the claim construction, the scope of a patent right after a PTE, and how the extension period should be calculated. In particular, questions surrounding pharmaceutical PTEs are governed by rules unique to Japan’s patent system. This article introduces the IPHC’s decision while also explaining relevant aspects of the Japanese legal framework.

Case summary

Plaintiff and Plaintiff’s Product

The plaintiff and (later) appellant (“Plaintiff”) is the patentee of JP Patent No. 3531170 (“the Patent”) and the marketing authorization holder of the originator pharmaceutical product.

The Plaintiff’s originator product (“Plaintiff’s Product”) discussed in this case is “REMITCH® OD Tablets 2.5 μg”, for which the description in the package insert is “active ingredient (有効成分): nalfurafine hydrochloride 2.5 μg (2.32 μg as nalfurafine) per tablet”.

Defendants and Defendants’ Product

The accused products (“Defendants’ Product”) are “Nalfurafine Hydrochloride OD Tablets 2.5 μg / [company name of each Defendant]”. They are generics of the Plaintiff’s Product, each containing nalfurafine hydrochloride 2.5 μg as the active ingredient (note: the description in the package insert is “active ingredient (有効成分) per tablet: nalfurafine hydrochloride 2.5 μg (2.32 μg as nalfurafine)”).

Plaintiff’s Claim

The Plaintiff alleged that the manufacture and sale of the Defendants’ Product infringed the Patent, for which a PTE had been registered. The Plaintiff therefore sought damages against the Defendants.

Patent Invention

The invention at issue (“the Patent Invention”) was Claim 1 of the Patent, which recites as follows:

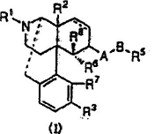

“An antipruritic agent comprising, as its active ingredient, an opioid κ receptor agonist compound represented by the general formula (I)”.

The structural formula (I) depicts the free form of nalfurafine.

PTE Registration

The Patent was granted a PTE registration (PTE Application No. JP2017-700154, “the PTE Registration”) based on the marketing authorization (“the Underlying MA”) issued on March 30, 2017 for the Plaintiff’s Product. The PTE Registration extended the patent term by approximately 4 years and 11 months (from the original November 2017 expiration to around October 2022). By the time of the IPHC decision, the extended term had already expired, and therefore an injunction was not at issue on appeal.

In the first instance, the Tokyo District Court found no infringement and dismissed the Plaintiff’s claims. The Plaintiff appealed to the IP High Court, which led to the present decision.

The Tokyo District Court denied infringement in the first instance

In the first instance, the parties argued several issues, including the scope of the patent right after PTE. The District Court focused primarily on the interpretation of the claim language, in particular the term “active ingredient (有効成分)”, and adopted the following construction:

- The term “active ingredient (有効成分)” in the claim refers to the active pharmaceutical ingredient (原薬) (“API”) that serves as the basis for formulating the final drug product by adding excipients. In other words, the free form of nalfurafine should be regarded as the API to formulate the antipruritic agent of the Patent Invention; and

- A formulation using a salt form of nalfurafine as the API does not fall within the claimed scope of the Patent Invention.

On this basis, the District Court held that the Defendants’ Product, formulated using nalfurafine hydrochloride as the API, did not fall within the literal scope of the claimed invention and therefore did not infringe the Patent. The Plaintiff’s claims were dismissed (Tokyo District Court, Mar. 30, 2021).

The District Court reasoned that, based on evidence literature, drug formulations in the pharmaceutical field commonly employ APIs in the form of free-base crystals or crystalline hydrates and salts, to which excipients are added to obtain the final dosage form. Accordingly, a person skilled in the art, upon reading the specification of the Patent (“the Specification”) that concerns an invention relating to “an active ingredient” to formulate “an antipruritic agent”, would ordinarily understand the term “active ingredient (有効成分)” to refer to the API used as the basis for formulating the drug. On this basis, the court denied literal infringement.

The District Court also rejected infringement under the doctrine of equivalents (“DOE”). It noted that the Specification expressly discloses, in addition to the compound described in the Patent Invention, pharmaceutically acceptable acid-addition salts thereof, also explicitly describing specific examples of such salts (such as hydrochloride, sulfate, and nitrate salts). The court found that this demonstrated an intentional exclusion of the salt forms from the claimed scope, thereby failing the fifth requirement of the Japanese DOE test (the “no intentional exclusion” requirement). Accordingly, DOE infringement was denied.

For reference, the Japanese DOE, developed through case law, requires the following five elements to be satisfied:

[cf. Five requirements for DOE infringement under Japanese case law]

(i) The differing element is not an essential part of the patented invention.

(ii) With respect to the differing element, the patented element can be replaced with the corresponding element of the accused product while still achieving the purpose of the patented invention and producing the same function and effect.

(iii) A person skilled in the art, at the time the accused product was made, could have easily conceived such a replacement.

(iv) The accused product was not publicly known or used at the time of filing.

(v) The differing element used in the accused product is not something that was intentionally excluded from the claimed scope during prosecution.

The IP High Court reversed the first instance decision

In contrast to the District Court, the IPHC held that:

- the Defendants’ Product falls within the technical scope of the patented invention;

- the extended patent right, after the PTE Registration, validly covers the manufacture and sale of the Defendants’ Product; and

- the PTE Registration itself is valid.

On grounds including these, the IPHC overturned the first instance and found infringement of the Patent.

Sections 5–7 below provide a detailed overview of the IPHC’s reasoning on each point.

Claim interpretation of “Active Ingredient (有効成分)” in the IPHC ruling

In its construction of the claim language, the IPHC adopted the interpretation that the claimed term “active ingredient (有効成分)” refers to “the substance that dissolves in the body (in the bloodstream) and exerts the pharmacological effect”.

The IPHC’s reasoning may be summarized as follows (i–v):

(i) Although Claim 1 does not employ the expression “κ receptor agonist compound or its salt” as the active ingredient, the Specification describes “opioid κ receptor agonists” as “morphinan derivatives exhibiting opioid κ receptor agonistic activity or their pharmaceutically acceptable acid-addition salts”, and contains references such as “opioid κ receptor agonist compound represented by general formula (I)” and its “acid-addition salts”. Also, in Example 9, the Specification mentions “morphinan hydrochloride 7, … a selective κ receptor agonist opioid compound” without strictly distinguishing between the compound and its acid-addition salts.

(ii) The evidence literature shows that, around the time of filing of the Patent, the term “active ingredient (有効成分)” was generally used in the field to refer to the chemical substance that dissolves in the body (in the bloodstream) and exhibits the pharmacological effect. There is no basis in the Specification to apply a different interpretation.

(iii) It is true that, from the standpoint of formulation development, the salt form of a compound may be used as the API to obtain the desired solubility or stability, and such salt forms may be referred to as the “active ingredient (有効成分)” to distinguish them from excipients. However, the added salt moiety itself does not exert the pharmacological effect in the body.

(iv) The purpose of the Patent Invention is to provide an antipruritic agent comprising an opioid κ receptor agonist exhibiting rapid and potent antipruritic activity. It was common general knowledge at the time of filing that acid-addition salts were often employed to improve solubility and stability. Nothing in the Specification suggests that the salt form has any technical significance beyond improving solubility or stability. Accordingly, a skilled person would easily understand that the substance exerting the antipruritic effect is the κ receptor agonist compound itself, and that the salt form is merely a form used to improve pharmaceutical properties (solubility and stability), without altering the underlying pruritic-relieving pharmacological action. Even if salt forms may sometimes be referred to as the “active ingredient (有効成分)” in the regulatory context or drug development field to distinguish them from excipients, a skilled person would not interpret the claimed phrase “antipruritic agent comprising, as its active ingredient, an opioid κ receptor agonist compound” as excluding the salt forms from the scope of the claim, only because it does not explicitly mention salts. It would be unnatural to construe, without a rational basis, a pharmaceutical claim as intentionally excluding the commonly used salt forms that improve solubility and stability. Rather, it is easily understood from the Specification that the salt forms constitute one embodiment of an antipruritic agent comprising the claimed κ receptor agonist compound.

(v) The prosecution history does not indicate that the applicant intentionally excluded “acid-addition salts” from Claim 1.

A brief explanation of prosecution history would be useful to supplement point (v). Prior to amendment, the claims read:

- Old Claim 1: “An antipruritic agent comprising an opioid κ receptor agonist compound as its active ingredient”.

- Old Claim 2: “The antipruritic agent of Claim 1, wherein the opioid κ receptor agonist compound is a morphinan derivative or its pharmaceutically acceptable acid-addition salt”.

- Old Claim 3: “The antipruritic agent of Claim 2, wherein the morphinan derivative is represented by formula (I)”.

In the amendment, Claims 1 and 2 were deleted, and old Claim 3 was amended to become current Claim 1. In this process the phrase “or its pharmaceutically acceptable acid-addition salt” disappeared. The IPHC noted that old Claim 3 (now Claim 1) had never been the subject of rejection, and the applicant (the Plaintiff) did not explain in the opinion letter the omission of the salt-language in the present Claim 1, and thus concluded that there was no indication of intentional exclusion.

After considering the claim language, the Specification, the prosecution history, and common general knowledge as of the filing as above, the IPHC concluded that the Patent Invention encompasses antipruritic agents in which the compound represented by formula (I), irrespective of whether it takes the salt form, dissolves in the body, is absorbed, and exerts its pharmacological effect based on its κ receptor agonistic properties. On this basis, the IPHC held that the Defendants’ Product that contains nalfurafine (although in hydrochloride salt form) that dissolves in the body and exhibits antipruritic activity, falls within the technical scope of the Patent Invention.

The IPHC’s decision on the scope of an extended patent right

The Patent at issue was subject to a PTE by the PTE Registration. Even if the Defendants’ Product falls within the literal scope of the claim, the scope of an extended patent right in Japan is narrowed down pursuant to Article 68-2 of the Patent Act. Accordingly, the next step in the analysis is to determine whether the manufacture and sale of the Defendants’ Product fall within the restricted scope of the patent right after the PTE.

This article first provides a brief overview of the Japanese PTE framework and the standards for determining the scope of an extended patent right provided by the 2017 IPHC Grand Panel decision of the IPHC, then explains the IPHC decision in the present case.

(1) Patent Term Extension (PTE) system in Japan

Article 67(4) of the Patent Act permits a patent term to be extended for up to five years “when there is a time period during which the patented invention could not be worked because the patentee was required to obtain a regulatory approval or license designated by Cabinet Order”. A marketing authorization for pharmaceuticals constitutes such a designated regulatory approval.

The key features of Japan’s PTE system are as follows:

(i) A PTE is applied for and is granted based on each corresponding marketing authorization.

(ii) A single patent may be granted with multiple PTEs. For example, two PTEs can be registered based on the initial marketing authorization as a brand-new drug and an approval for an addition of indication.

(iii) Conversely, a single marketing authorization may serve as the basis of PTE for multiple patents.

(iv) After extension, the patent right does not cover the entire claim scope. Article 68-2 of the Patent Act stipulates that the extended patent right is effective only with respect to the working of the patented invention on the item specified as the subject of the required disposition that constitutes the grounds for the extension registration (and, where the approval specifies a particular use of the item, only for that use). In the pharmaceutical context, the required disposition means the marketing authorization.

(2) The standard for determining the scope of patent rights during PTE provided by the 2017 Grand Panel decision of the IPHC

The leading authority regarding the standard to determine the restricted scope of patent rights during PTE under Article 68-2 of the Patent Act is the 2017 IPHC Grand Panel decision (Jan. 20, 2017, 2016 (Ne) No. 10046, known as the “Oxaliplatin Case”).

The Grand Panel held that the extended patent right is effective only with regard to the workings of the patented invention on:

(i) a product identified by the “ingredients (not limited to API), strength, dosage and administration, and indication” specified in the underlying marketing authorization; as well as

(ii) products that are “substantially the same” as such product.

The Grand Panel further provided guidance on how to evaluate the “substantially the same” requirement, particularly for patent inventions directed to pharmaceutical ingredients. It explained that, in a limited case where differences between the approved product and the accused product relate only to differences in ingredients, or numerical differences in amount, or dosage and administration, and no other differences exist, substantial identity should be determined by comparing the technical features and functions/effects of both products in light of common general technical knowledge. It then provided the following four illustrative categories in which “substantial identity” may be recognized in such limited case:

- For inventions characterized solely by their active ingredient: where the accused product differs only by the addition/substitution of other non-active ingredients based on common, conventional techniques at the time of their marketing authorization.

- For inventions relating to stability or dosage forms of a known active ingredient: where differences arise from the partial addition/substitution of ingredients based on common, conventional techniques at the time of their marketing authorization, and the technical features and effects remain the same.

- Where the quantitative differences in the amount or dosage are insignificant.

- Where the strength specified in the marketing authorizations are different, but practically the same when considering dosage and administration together.

(3) The IPHC decision on the scope of an extended patent right in the present case

In the present case, when comparing the Plaintiff’s Product (as identified by its ingredients, strength, dosage and administration, and indications in the Underlying MA) with the Defendants’ Product, the active ingredient and its strength (nalfurafine hydrochloride, 2.5 μg) are identical. The dosage and administration, indications, as well as dosage form (OD tablets) are also identical. By contrast, the excipients consist of different combinations.

Following the same analytical framework as in the 2017 IPHC Grand Panel Judgment, the IP High Court held that the scope of an extended patent right encompasses not only products whose “ingredients, strength, dosage and administration, and indications” as a pharmaceutical are identical to those of the Plaintiff’s Product, but also those that are deemed substantially identical thereto.

Based on this framework, the IPHC found as follows and concluded that the Defendants’ Product is substantially identical to the Plaintiff’s Product despite the above compositional differences, and that the extended patent right covers the manufacture and sale of the Defendants’ Product.

i) The IPHC characterized the patented invention as a use invention in which the technical feature lies in providing a new usage of “a κ receptor agonist compound represented by General Formula (I)”, which was already publicly known as a compound per se at the time of filing, as an active ingredient exhibiting an antipruritic effect. The IPHC then presented the following criteria for determining the scope of “substantial identity” under Article 68-2 of the Patent Act governing the scope of an extended patent:

Where the accused product and the Plaintiff’s Product share the same technical feature and effect in that both are antipruritic agents using nalfurafine as the active ingredient, and where they also share the same specific dosage form as pharmaceuticals, the following cases (a) and (b) should be regarded as substantially identical to the Plaintiff’s Product as the subject of the Underlying MA:

a. Cases where the accused product differs only in that certain non-active ingredients have been added, replaced, or otherwise modified based on publicly known and conventional techniques at the time of its approval application; or

b. Cases where differences in ingredients, etc., other than in the active ingredient, do not affect the indications of the pharmaceutical and are considered to constitute only minor differences or merely formal differences when viewed as a whole.

ii) With respect to the differences in excipients between the Plaintiff’s Product and the Defendants’ Product, the IPHC stated the following and held that the Defendants’ Product falls within the scope of products substantially identical to the Plaintiff’s Product as the subject of the Underlying MA:

- According to the evidence literature, it is common technical knowledge that excipients do not exhibit pharmacological effects and do not interfere with the therapeutic efficacy of the active ingredient.

- The claims of the Patent Invention do not specify any excipients contained in the antipruritic agent. The Specification merely states that the κ receptor agonist may be formulated into a pharmaceutical composition by mixing with carriers, excipients, etc., for oral or parenteral administration, and provides some description of the content of the κ receptor agonist in oral formulations.

- The Plaintiff’s Product and the Defendants’ Product share the same technical feature and pharmacological effect as antipruritic agents using nalfurafine as the active ingredient, and also share the same specific dosage form as pharmaceuticals. In light of these commonalities and the above-stated nature of excipients, the differences in excipients between the Plaintiff’s Product and the Defendants’ Product constitute only minor, or overall, merely formal differences.

iii) With respect to this point, the Defendants argued that in their formulations, they did not merely rely on publicly known or conventional techniques but instead used their own uniquely developed group of excipients, developed with particular focus on the stability of the active ingredient within the formulation, and that this should preclude a finding of substantial identity. Nevertheless, the IPHC rejected this argument as follows. This corresponds to case (b) under the criteria set forth in section (i) above:

- The Plaintiff’s and Defendants’ formulations are both orally administered OD tablets using nalfurafine as the active ingredient for an antipruritic agent, and therefore share the same technical feature, pharmacological effect, and dosage form as pharmaceuticals. By contrast, the excipients in the Defendants’ formulations do not exhibit pharmacological activity, are harmless, and are added as substances that do not interfere with the therapeutic efficacy of nalfurafine.

- Even if the Defendants’ formulations use a group of excipients independently developed by the Defendants and even if such excipients were the subject of separate patent filings, this does not change the fact that the excipients do not have pharmacological effects and do not interfere with the therapeutic efficacy of nalfurafine. Accordingly, this is insufficient to find that the substantial identity of the Plaintiff’s Product and the Defendants’ Product, viewed from the standpoint of Article 68-2 of the Patent Act as pharmaceuticals, is affected.

The validity and extension period of the PTE Registration

The present IPHC decision

In the present infringement litigation, the Defendants also challenged the validity of the PTE Registration itself and the length of the extension period. The IPHC rejected both arguments.

Under the Patent Act (Article 67(4) and Article 67-7(1)(i) and (iii)):

- A registration of PTE is valid when the marketing authorization (which forms the basis for the PTE registration) needed to be obtained in order to work the patented invention; and

- The period eligible for extension is defined as “the period during which the patented invention could not be worked because of the need for obtaining the marketing authorization”.

Under the established case law, this period begins on the later of (i) the date on which the applicant commenced the studies necessary for obtaining the marketing authorization, or (ii) the date of registration of the patent, and ends on the day immediately preceding the date on which the marketing authorization was notified to the applicant.

The Underlying MA forming the basis for the PTE Registration is the marketing authorization for the Plaintiff’s Product, REMITCH® OD Tablets 2.5 μg. Prior to that authorization, the Plaintiff already had an approved product, REMITCH® Capsules 2.5 μg. The Underlying MA for REMITCH® OD Tablets 2.5 μg was an authorization for adding a new dosage form.

The PTE Registration recognized, as the extension period, (a) the period required for the bioequivalence studies between the OD tablets and the capsule formulation that were submitted for the dosage-form addition in the Underlying MA, combined with (b) the period for the clinical studies conducted using the capsule formulation which had been reviewed at the time of the capsule authorization but were also submitted as part of the application materials for the OD tablets. The IPHC held that this PTE Registration and the calculation of the extension period were valid and appropriate.

The Defendants argued that, because another PTE had already been registered based on the authorization for the capsule formulation, including period (b) again here in the PTE Registration resulted in double-counting. The IPHC rejected this argument, holding that: (i) the studies in (b) were necessary for obtaining the authorization for the OD tablets at issue and were in fact reviewed as submitted data for that application; and (ii) the mere existence of the capsule authorization did not enable the patentee to work the present patented invention for the OD tablet dosage form, i.e., the Plaintiff’s Product. (Note: Under Article 68-2 of the Patent Act, the scope of the patent right as extended based on the capsule authorization would not extend to the OD tablet dosage form).

The entire dispute

In fact, in the bigger picture, the overall background of this dispute involves a more complex series of legal actions. In parallel with the present infringement litigation explained in this article, there were also multiple administrative proceedings before the JPO reviewing the validity of the relevant extension registrations (including the PTE Registration) and the patent validity, with subsequent appeal litigations thereon before the IPHC.

With respect to the present PTE Registration, the JPO had first rejected the registration, and such JPO’s administrative decision was challenged through administrative proceedings, separately from the present infringement action. Although the JPO Trial Board initially refused the PTE Registration, in the revocation proceedings the IPHC held that the PTE Registration should be granted, overturning the JPO’s decision. Notably, this IPHC judgment was rendered in March 2021, immediately before the first-instance judgment in the infringement action. At that time, the reasoning in the infringement case (the District Court’s claim construction finding non-infringement) and the IPHC judgment in the administrative appeal concerning the PTE Registration (which accepted the extension based on the Underlying MA for a product containing nalfurafine hydrochloride as its API) were difficult to reconcile. Eventually, the IPHC overturned the first-instance decision as explained above, thereby aligning the outcomes.

Now, the appeal against the IPHC judgment in this infringement case, as well as an appeal in the administrative proceedings regarding the validity of the PTE Registration (arising from an invalidation trial filed by a Defendant), has been filed with the Supreme Court. The IPHC decisions, therefore, are pending before becoming final and binding.

Conclusion

While waiting for the final determination depending on the Supreme Court’s judgment, one of the important implications of the present IPHC decision is that it provides additional guidance, beyond the 2017 IPHC Grand Panel decision, on how to determine the scope of an extended patent right, particularly in cases involving use inventions (i.e., inventions claiming a product for use in a newly discovered use of a known substance). Given that rights enforcement by originator pharmaceutical companies against generic manufacturers often occurs during the extended patent term, and that use-invention claims are commonly employed in pharmaceutical patents, the practical significance of this decision is substantial.

As for the interpretation of “active ingredient (有効成分)”, claim construction is a process that may vary depending on the specific circumstances, such as the wording used in other parts of the claim, the statements in the specification, and the prosecution history. Therefore, it may not be appropriate to broadly generalize the IPHC’s construction of “active ingredient (有効成分)” as a universally applicable rule. Nevertheless, the decision may well influence future interpretations of terms in claims with similar expression patterns, as well as practical approaches to claim and specification drafting at the time of filing.

Relevant Articles

This article discusses a dispute between manufacturers of originator and generic pharmaceuticals in Japan. Here are some previous articles on the relevant topic, by the same author and available in English:

- Recent IP High Court Decision regarding the Patent Linkage System in Japan (TMI NEWSLETTER Issue 27)

- When Does a Generic Entry Become Possible? - patent protections and pharmaceutical regulations in Japan (TMI NEWSLETTER Issue 17)

Author: Sayaka Ueno

Member

PROFILE